I have a guest priest from Cross Catholic International coming to celebrate the Sacrament of Reconciliation and all the Masses this weekend, so I have a reprieve from preparing a Sunday homily this week. So I thought, rather than skipping my blog for this weekend (which was very tempting!), I decided to read through my usual commentaries and sources, and put something together. As it happens, there were some interesting thoughts I wanted to comment on. So rather than offer a homily for the Sunday Mass, I would like to share my thoughts about our Gospel Reading.

James and John, the sons of Zebedee, came to Jesus and said to him,

“Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.”

He replied, “What do you wish me to do for you?”

They answered him, “Grant that in your glory

we may sit one at your right and the other at your left.”

Jesus said to them,

“You do not know what you are asking.

Can you drink the cup that I drink

or be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?”

They said to him, “We can.”

Jesus said to them,

“The cup that I drink, you will drink,

and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized;

but to sit at my right or at my left is not mine to give

but is for those for whom it has been prepared.”

When the ten heard this, they became indignant at James and John.

Jesus summoned them and said to them,

“You know that those who are recognized as rulers over the Gentiles

lord it over them,

and their great ones make their authority over them felt.

But it shall not be so among you.

Rather, whoever wishes to be great among you will be your servant;

whoever wishes to be first among you will be the slave of all.

For the Son of Man did not come to be served

but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

This reading for Sunday follows immediately upon Jesus giving his third prediction of his Passion, Death, and Resurrection, which fell in the gap between last Sunday’s reading and today’s reading. In today’s reading, Jesus asks James and John, “Can you drink the cup that I drink or be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” Jesus brings together two images very important in Christian Tradition.

Can you drink the cup that I drink…

When does a cup come up? Well, it came up the night before the crucifixion at the Last Supper, when Jesus took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to his disciples, and said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed for many. Amen, I say to you, I shall not drink again the fruit of the vine until the day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.” Dr. Scott Hahn has an excellent reflection on the concept of “The Fourth Cup.”

“There are four cups that represent the structure of the Passover. The first cup is the blessing of the festival day, it’s the kiddush cup. The second cup of wine occurs really at the beginning of the Passover liturgy itself, and that involves the singing of psalm 113. And then there’s the third cup, the cup of blessing which involves the actual meal, the unleavened bread and so on. And then, before the fourth cup, you sing the great hil-el psalms: 114, 115, 116, 117 and 118. And having sung those psalms you proceed to the fourth cup which for all practical purposes climaxed and consummated the Passover. Now what’s the problem? The problem is that gospel account says that after the third cup, Jesus says, “I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I am entering into the kingdom of God.” And it says, “Then they sang the psalms.”

So what happens with the fourth cup? First, look at Gethsemane:

He fell to the ground and three times said to the Father, “Abba, Father… All things are possible to Thee. Remove this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what Thou wilt.” Remove this cup. What is this cup?

And then:

Jesus, on the cross, knowing that all was now finished said, in order to fulfill the scriptures, “I thirst.” Now, he’s been on the cross for hours. Is this the first moment of thirst? No, he’d been wracked with pain and dying of thirst for hours. But he says, in order to fulfill the scripture, “I thirst.” “They put a sponge full of the sour wine on hyssop and held it to his mouth. When Jesus had received the sour wine he said the words that are spoken of in the fourth cup consummation, “It is finished.” In Latin, “Consummatum est.” What is the “it” referring to? The “it” is the Passover sacrifice.

The Passover Sacrifice is now the Eucharistic Sacrifice. The Last Supper and the Crucifixion are joined by the Fourth Cup into the single event of Christ’s self-sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins. I said in an earlier post that Christ always predicted his crucifixion joined to his resurrection, as a single event. And so we have a triptych: Last Supper, Crucifixion, Resurrection. And every Mass is all three, the entryway for Christians of all generations to participate in this singular triptych event of the Bridegroom’s consummation once for all with His Bride. And it is at the celebration of the Mass that the Bride consummates throughout time with her Bridegroom, uniting herself to Him.

In the case of Jesus, the Fourth Cup, the “Cup of Consummation” is the consummation of the nuptial covenant of the Bridegroom with his Bride. There is an image of the cup of God’s wrath that Isaiah’s Suffering Servant must drink. By “drinking this cup,” Christ pays the price for the redemption of his Bride, winning her from Satan’s claim on her for her sins, so that she is free. She now belongs to Christ. For Christians, the question, “Can you drink the cup that I drink” is the “bitter cup” of suffering, of sacrifice, of persecution and rejection, the cup of the consequence of sin (ours and others’).

…or be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?”

In the blessing of the baptismal font, the priest or deacon recounts the many ways in which water was a sign of baptism throughout Salvation History. At the end of the blessing, he puts his hand into the water, and says, “We ask you, Father, with your Son to send the Holy Spirit upon the waters of this font. May all who are buried with Christ in the death of baptism rise also with him to newness of life. We ask this through Christ our Lord. Amen.” That’s a striking image: “buried with Christ in the death of baptism.” What is the “death of baptism”?

Adam and Eve had the vocation to be the parents of all the living, and to pass on to all humanity their relationship of peace and one-ness with themselves, with each other, with God, and with all Creation. But because of their sin, their vocation was corrupted, and instead they handed on to all humanity their broken relationship within themselves, and with each other, with God, and with all Creation.

Jesus came to give us life, and life abundant, by giving us participation in his life, and his relationship with the Father: to restore to us what we lost, and more. We always have to remember that uniting ourselves to the life of Jesus is not just the resurrection, but the cross as well. So Christian baptism is the death of that disordered spiritual life we inherited from Adam and Eve, the death of sinful habits, disorders, desires, attachments, and scripts of reacting to circumstances sinfully, to be replaced by new ways of living, seeking first the Kingdom of God, and responding to circumstances with grace. It is the death of the broken communion within ourselves, and in our relationships. So the “death of baptism” is the death of all that is from Satan, through Adam and Eve, that is not from God.

So when Jesus asked James and John, “Can you drink the cup that I drink or be baptized with the baptism with which I am baptized?” he was asking them if they were prepared to even pay the price to enter the Kingdom–to accept the bitter cup of suffering and the death of baptism–much less be seated at places of honor. Were they prepared to endure their passion and death, spiritually for certain, and physically perhaps, that is part of the Christian vocation, and required for being part of the Kingdom?

“They said to him, ‘We can.’ Jesus said to them, ‘The cup that I drink, you will drink, and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized; but to sit at my right or at my left is not mine to give but is for those for whom it has been prepared.'”

Jesus just before this told of his own Passion. Here, probably not understood by James and John, he foretold of theirs! Of course, it is held by Tradition that John was not martyred as were the other disciples, but he was exiled, a “living death” as his share of persecution, a “white martyrdom.”

So who sits at Jesus’ right and left in the Kingdom? We’ll have to wait until we get there to see. But here are two thoughts to consider. First, in the ancient Kingdom of God under King Solomon, the Queen Mother sat enthroned to the right of her son, to carry out her privileged role of interceding with her royal son on behalf of his humble people who implored her help to receive his grace. So perhaps we know who sits to Jesus’ right. But here’s another thought. When Jesus entered into his glory–his “hour of glory”–who were at his right and at his left? Two criminals, who were paying the debt for their crimes. I’m not presuming to say that these two are at the right and left of Jesus at his heavenly throne. But while St. Dismas—the name Tradition gives to the “repentant thief,—is traditionally portrayed as being on Jesus’ right (because good was on the right, and bad on the left), the Scriptures don’t say which side was which. Perhaps St. Dismas is on the left, and the Blessed Mother is on the right. Or perhaps you will be on the left! St. Chrysostom drops the whole question: “No one sits on His right hand or on His left, for that throne is inaccessible to a creature.” Again, we’ll just have to wait and see!

Before I leave the subject of the (Eucharistic) cup and Baptism and move on with the rest of the Gospel reading, I want to note that there is a tradition of another association between them.

Before the Jewish wedding ceremony, there was the tradition of the ritual bridal (or nuptial) bath, in which the bride would cleanse herself in preparation for the wedding feast (which ended with the wedding consummation!).

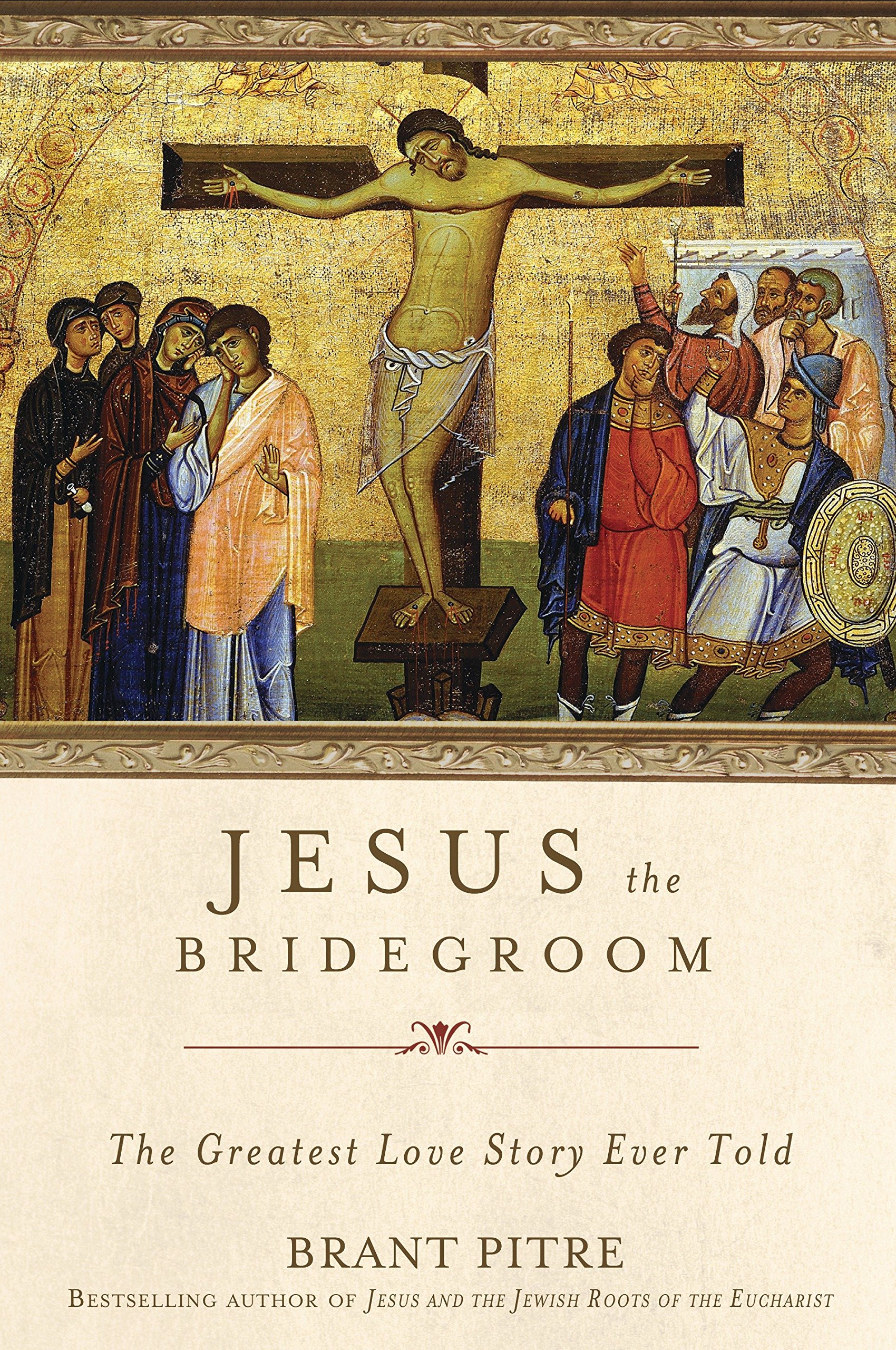

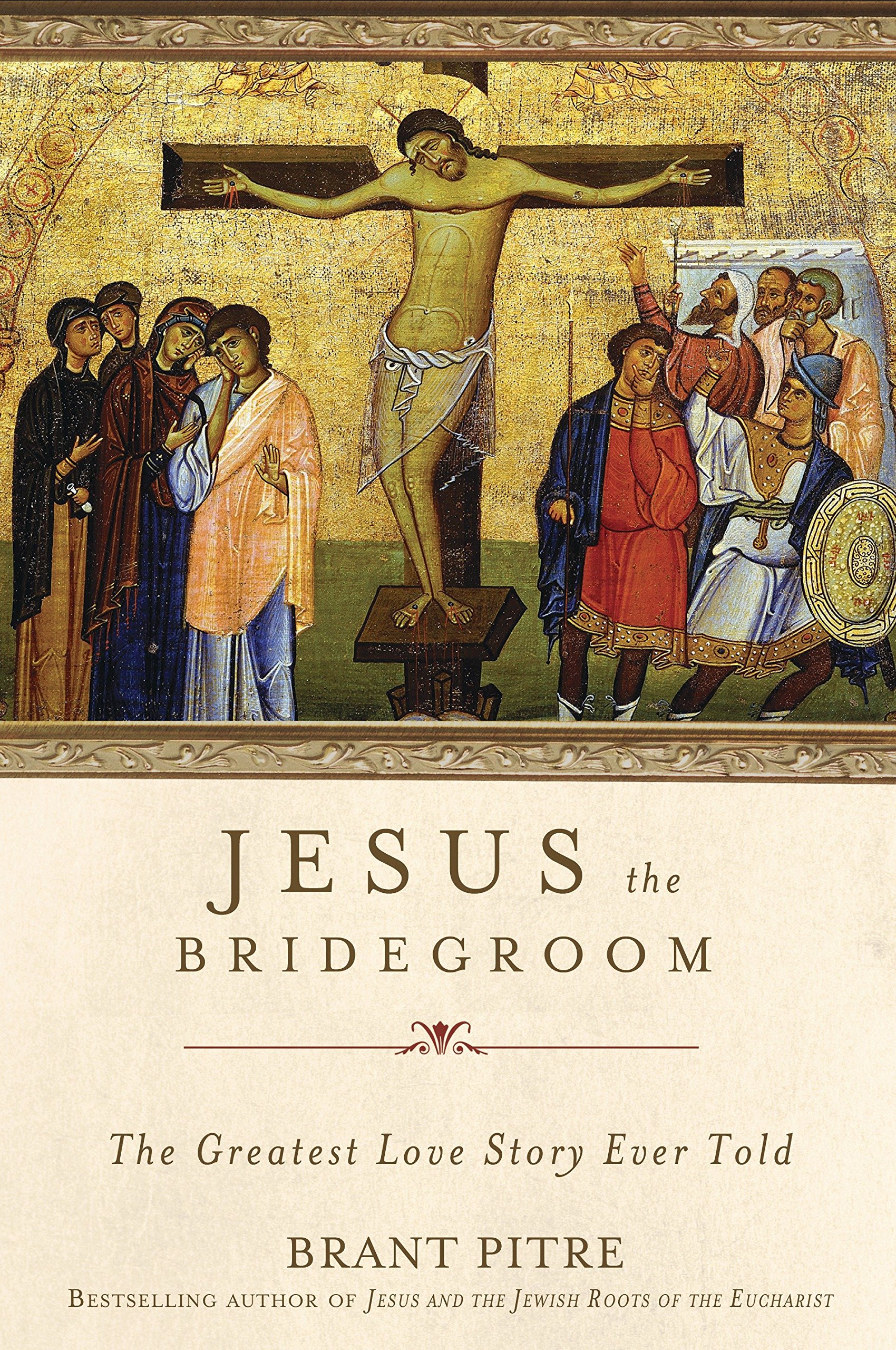

In Brant Pitre’s Jesus the Bridegroom: The Greatest Love Story Ever Told, he describes each new member of the Church being incorporated into the person of the Bride as she enters into the nuptial bath of baptism, which cleanses her of her sins, to prepare her for her consummation with her Bridegroom in the wedding feast of the Eucharist. So in baptism, we receive the washing of forgiveness of sins, and become members of the Church, the Bride of Christ, and we are prepared to participate in the Eucharist, the communion of the Bride and the Bridegroom.

And of course, the Church fathers were quick to draw the connection between the blood and water that flowed from the pierced heart of the crucified Christ and the sacraments of the Eucharist and Baptism. The Book of Revelation introduces the saints as they who “have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.” The Baptismal water is both a nuptial bath and the forgiveness of sins. The Blood of Christ both cleanses us of our sins and is the cup of salvation of the wedding feast of the Lamb and the Bride.

“The cup that I drink, you will drink, and with the baptism with which I am baptized, you will be baptized.” Christ drinks the cup of suffering that becomes the cup of our salvation. Christ is baptized into death, which becomes our baptism into new life. We do drink the cup that he drinks, and we are baptized with his baptism, because through Christ, his suffering and death become our communion with him and the life of grace!

“You know that those who are recognized as rulers over the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones make their authority over them felt. But it shall not be so among you. Rather, whoever wishes to be great among you will be your servant; whoever wishes to be first among you will be the slave of all. For the Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve…”

No doubt most people have had to suffer under someone in authority who was all about themselves and their exercise of power and will. History, including the present, has more than a few tyrants and despots and dictators and corrupt leaders. But Christian leaders are called to be leaders who act in accord with Christ, who have both Christian conduct in their person and in their exercise of authority. And the greatest of these, of course, is love. There is an old maxim that a rich man should think of himself as a father of a large family, in terms of his generous, responsible stewardship of his wealth. Likewise, a Christian leader should think of himself as the father of a large, complex family, where the goal is the common good, the flourishing of every individual, and of the whole community, both at the same time. There may be times when the good of the many is stacked against the good of the one, but the one still has certain inviolable rights that must be regarded and protected.

After the minister (deacon or priest) baptizes a child, and as he prepares to anoint the child with chrism on the crown of his or her head, the minister says, “The God of power and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ has freed you from sin, given you a new birth by water and the Holy Spirit, and welcomed you into his holy people. He now anoints you with the chrism of salvation. As Christ was anointed Priest, Prophet, and King, so may you live always as a member of his body, sharing everlasting life.”

When we are baptized into his life, and into his relationship with the Father, we are also baptized into his job. I mentioned a few weeks ago about Christ in the role of Priest, Prophet, and King. What does he show us about living out these roles?

- As priest, He offers prayer and sacrifice, He glorifies the Lord and intercedes for the needs of the people, He blesses the world by His example of virtue and wisdom, and He calls the world to repentance and conversion.

- As prophet, He speaks the divine truth, in season and out of season, He invites others into life in the Truth, into life in relationship with the Father; He suffers, He endures ridicule and shame, He turns the other cheek to those who insult Him.

- As king, He shows us that divine power becomes poor that we might become rich; as One who is great He becomes the least and the servant of all; He lifts up the lowly, He feeds the hungry, He welcomes the stranger, He clothes the naked, He cares for the sick, He gives to the poor; as the greatest He becomes the smallest, and concerned about the smallest, the weakest, and most vulnerable.

Today’s gospel has to do with that last part. We are sons and daughters of the most high God, we are princes and princesses of all of Creation, our father’s realm. And we are expected to carry out our royal duties with diligence and grace. Christ gave us the example of what it means to exercise divine power… from his throne of the cross. This is where he showed his great love for creation, and humanity in particular. He didn’t need to have a heavy hand, because divine power is merciful. He didn’t need weapons and violence, because divine power is gentle. He didn’t need to defend his rights or shout his commands, because divine power is humble. He prayed for the forgiveness of his persecutors, and laid down his life for his friends, because divine power is love.

“…and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

The Greek word at the end of that sentence is pollōn. It’s the same word as in the phrase, “you are more valuable than many sparrows,” and “I wrote to you with many tears.” It is literally and truly the word for “many,” and not the word for “all.” In Latin, it is translated the same: “pro multis.” It is the same word in the Institution narrative: “This is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed for many.” And now, as of the 2011 updated English translation of the Roman Missal, it is the same translation in the consecration of the Precious Blood on the altar in the Mass, “…poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sin.”

You might remember that there was much wailing and gnashing of teeth at the correction of the translation from the earlier version, “poured out for you and for all.” That might sound wonderfully inclusive, but it’s not what Jesus said in the Gospel. But there are two good and valid ways to handle this.

First, the scriptural and linguistic way. It is unfortunate that the attention was on the contrast between “many” and “all,” because that really was the wrong question. The contrast is between the one and the many. The commentary in the New American Bible (the translation that is the basis for the Lectionary), has a note that says, “Many does not mean that some are excluded, but is a Semitism designating the collectivity who benefit from the service of the one, and is equivalent to ‘all.’” The Catechism says in paragraph 605,

“He affirms that he came “to give his life as a ransom for many”; this last term is not restrictive, but contrasts the whole of humanity with the unique person of the redeemer who hands himself over to save us. The Church, following the apostles, teaches that Christ died for all men without exception: “There is not, never has been, and never will be a single human being for whom Christ did not suffer.”

Second, the consequential and free-will way. While it is true that Christ died for all, not all will choose to benefit by this gift. Some will refuse the gift, and choose hell. Some will not be saved. Not because Christ’s sacrifice was restrictive and not meant for them, but because they restricted themselves out of being saved by Christ’s sacrifice by their own choice. God wants that all be saved. But not all want themselves to be saved. And so we have in the preface of the fourth Eucharistic Prayer, “yet you, who alone are good, the source of life, have made all that is, so that you might fill your creatures with blessings and bring joy to many of them by the glory of your light.” That sounds much more like a restrictive use of the word “many”—as opposed to “all.”

So before I sign off, I wanted to make a little announcement, particularly because I evidently have a little audience. Last weekend I wanted to reference at dinner something I wrote, and accessed my site for the first time using a cell phone, which wasn’t logged into WordPress, and I was appalled by how it looks to a viewer, to you. Shocked, I tell you.

So I went ahead and paid for the subscription service that knocks out all the ads, and opens up some new options. I explored every one of the free themes they offer, and I didn’t really like any of them enough to change the layout. I would prefer a side bar of widgets, but I’m not willing to give up what I have to get it (or pay more to be able to modify the current theme).

Also, you might notice that the website changed. I have my own domain!! How cool is that!? You might not have noticed, but you are now at http://www.snarkyvicar.com! And if that weren’t the bees knees, I got a new email address: steve@snarkyvicar.com (which works like a gmail suite pseudo-business account, with half the bells and whistles). So I’m pretty excited, and I want to thank YOU for the likes, the loves, the shares, the comments, and the support and encouragement. And of course, the friendship!

Galilee, in the low-lying farm-land of the north. Elizabeth lives in the mountainous hill country of Judea, in the south. It took a week or so for Mary to make the journey, where she stayed for three months. This means that when these two holy children encountered each other—the unborn infant John, in his mother Elizabeth’s womb, and the unborn Lord Jesus, the fruit of his mother Mary’s womb—John was about 24 weeks old, and Jesus was barely more than 10-14 days old—neither of whom are considered persons with the dignity of human life by our own country’s laws. But we’re not going in that direction today… that’s a homily for later.

Galilee, in the low-lying farm-land of the north. Elizabeth lives in the mountainous hill country of Judea, in the south. It took a week or so for Mary to make the journey, where she stayed for three months. This means that when these two holy children encountered each other—the unborn infant John, in his mother Elizabeth’s womb, and the unborn Lord Jesus, the fruit of his mother Mary’s womb—John was about 24 weeks old, and Jesus was barely more than 10-14 days old—neither of whom are considered persons with the dignity of human life by our own country’s laws. But we’re not going in that direction today… that’s a homily for later.

In 1858, a few years after Pope Pius’ proclamation of this dogma, the Blessed Mother

In 1858, a few years after Pope Pius’ proclamation of this dogma, the Blessed Mother

Pope Leo then composed and added the Saint Michael Prayer to the celebration of the Mass, to ask his intercession for the protection of the Church and her people, built on this Old Testament image of Michael as the prince and protector of the People of God.

Pope Leo then composed and added the Saint Michael Prayer to the celebration of the Mass, to ask his intercession for the protection of the Church and her people, built on this Old Testament image of Michael as the prince and protector of the People of God.

The prophet Elijah was on the run from the lukewarm king Ahab and his wicked queen Jezebel, and God directs Elijah to the pagan city of Zarephath. At the entrance of the city, he sees this widow. I always get a little kick out of this dialogue, because this widow and her son are down to nothing, one last little morsel before they die of starvation. And Elijah tells her, yeah, ok, but first make me a cake.

The prophet Elijah was on the run from the lukewarm king Ahab and his wicked queen Jezebel, and God directs Elijah to the pagan city of Zarephath. At the entrance of the city, he sees this widow. I always get a little kick out of this dialogue, because this widow and her son are down to nothing, one last little morsel before they die of starvation. And Elijah tells her, yeah, ok, but first make me a cake.

Effective People

Effective People which happens to also be our first reading for today. Every Jew knew this passage by heart, like the way all Christians know Matthew 6:9-13 by heart. That’s the Our Father, which is part of the Church’s morning and evening prayer.

which happens to also be our first reading for today. Every Jew knew this passage by heart, like the way all Christians know Matthew 6:9-13 by heart. That’s the Our Father, which is part of the Church’s morning and evening prayer.

To borrow from Fr. Michael Schmitz (famed youth pastor and speaker for

To borrow from Fr. Michael Schmitz (famed youth pastor and speaker for

But one must also answer on judgment day for their Christian use of their wealth.

But one must also answer on judgment day for their Christian use of their wealth.