The Amish struggled with living out that forgiveness perfectly in their feelings, but their will, their chosen response, was to offer forgiveness, and did so automatically, as part of their cultural identity. They were amazed, they said, that we were amazed, at their immediate response to show forgiveness. To them, that was what it meant to be Christian. Many who lost children, or whose children were permanently scarred or disabled from the event, continue to will forgiveness against their occasional feelings of anger, but they also have the support of their families and community in their struggles. There continues to be a healthy, joy-filled, and love-filled relationship between the Amish community and the family of the gunman.

Many critics in the media (because that’s what they do) said that forgiveness came easier because the gunman was killed, and they didn’t have to deal with his fate. But in other crimes against the Amish community, they took great pains to go to court to plead for mercy for the perpetrators, especially when the death penalty was a consideration.

Forgiveness does not mean that the wrong-doer escapes any and all consequences for their actions; that itself would be injustice, and would not help to reform the wrong-doer. But it does mean that those who have been wounded refuse to nurture their anger and right to vengeance, in favor of seeking the reform of the wrong-doer, and a restoration, or even increase, of peace in the community.

We could learn something from the Amish in their response to wrong-doing, even egregious wrong-doing like a school shooting. We can offer forgiveness to Nikolas Cruze. We can seek his healing and salvation. We can choose not to nurture and expand our emotional response of wrath and vengeance, but ask God to heal our unforgiveness, and heal Cruze of the mental illness and wounds of his childhood that brought him to this situation. Yes, he chose to do this act, and he is accountable to the just and fair consequences of the act. But it is not just and fair to bring down on him our anger for being part of a larger rash of school shootings, and the failure of our society to serve and protect our children, and our mentally ill among us. (There is also the question about whether true justice, which includes mercy, ought to rightfully include killing the guilty, but that’s a separate discussion.) This forgiveness is not to suppress and sublimate our negative feelings, but to let them die of starvation, to let go of them, and turn our hearts back to the response we have chosen, instead of the feelings. I disagree with the Amish on many issues, but I think they have a lot to teach us about grace and forgiveness.

This is my last post and comment on the guns and school shooting topic. I don’t have the solution, except for the long-term solution of righting the host of deprivations and depravities which our society has tolerated and even celebrated. The ultimate solution is the conversion of hearts and minds to love and truth. But that will not stop those whose hearts and minds are deformed. And that—the concrete, short-term, urgent (before our next school shooting attempt) aspect of the solution—is where I bow out of the conversation. My expertise is neither guns nor law. My expertise is forgiveness, and the call to holiness, to divine truth and love, and that’s the long hard, narrow, uphill way, to ultimately solving this (and everything else). But to come up with the urgently needed solution that will protect our kids from the *next* shooter? I humbly defer to those with more wisdom in this matter. God bless you and protect you, and your families.

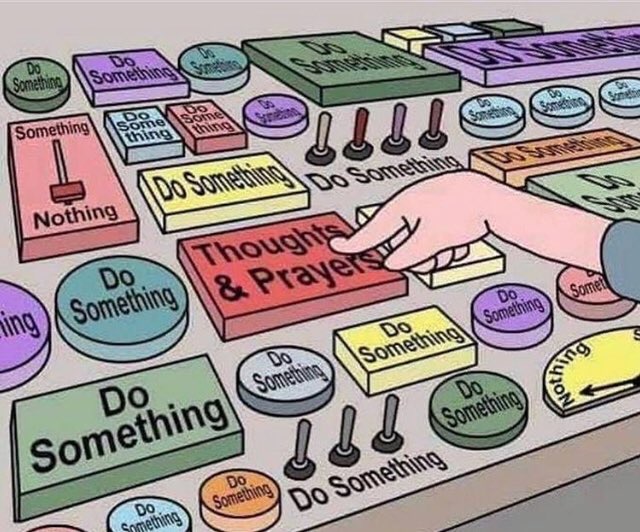

On Thoughts and Prayers

I’m writing this (ok, starting this) on February 15, the day after Ash Wednesday, as marked by the poignant picture of this woman, waiting in the parents’ and students’ area outside Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, still with her ashen cross emblazoned on her forehead. Social Media is, not unexpectedly, aflame with frustration over expressions of “thoughts and prayers for the victims” while, cynically and probably not incorrectly, another mass shooting fails to inspire any legislative response. This post isn’t about what political or legislative response we should hope for. It’s about the thoughts and prayers. And why people are frustrated with the expression.

We believe in the God who is Love, the God of Compassion, and of infinite Might and Power. But also a God who did not prevent His Son from being executed for political and religious motives, by those who should have rushed to worship Him rather than kill Him. He loved His Son perfectly, divinely, and with all the fullness of his own infinite nature. Sure, His Son was going to be resurrected after three days. But God isn’t three days ahead, He’s fully present to the reality of the present moment. And we cannot fathom or understand His experience at the agony and suffering and death of His Son incarnate.

We humans, whose love is hampered by our sinfulness and limitedness, still love others, most especially our children, with incredibly profound depths of love, self-sacrificing love. Which tells you something about God’s love, the perfect source of our imperfect love. As members of the Body of Christ, we share one another’s grief and pain, their joy and hope. When one member suffers, the other members of the Body share in that suffering. Even beyond the Body of Christ, our shared human identity connects us together in a natural bond. Our imagination tries to simulate what it must feel like to experience what they are experiencing. It allows us to empathize. And we can imagine what it might be like for those people whose children were killed or injured yesterday in Florida. Those who have children can empathize better than those who do not. Those who have lost children can perhaps empathize even better, but not perfectly.

Most of us “ordinary people,” meaning those without any significant and immediate capacity to directly respond to the events and people personally affected by this tragedy, we have this sense of sorrow for them, our empathy for them, our compassion for (suffering+with) them, and seemingly nothing productive to do with it. So we post on social media, “Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims of this tragedy.” And it is right and good to do so. We do believe in the power of prayer, and of the unity of all of us as beloved creatures (or Sons and Daughters) of the Most High God, made in His image (of Love) and likeness (of Holiness).

Fr. Mike Schmitz over at Ascension Press has an awesome video on the Power of Prayer and why we are called to pray, even though God’s already going to do what is best. We are called by our faith (and nature) to participate in the will of God the Father, and thus learn better the heart of the Father, and conform our hearts to His. God is with the brokenhearted, with the suffering and those who mourn, and so in prayer, we are, too. Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims. Jesus did not come to end suffering, but to be with us through every suffering of ours, to let us know we are never abandoned or alone, especially when we most feel like we are. To post to social media our identifying with the pain and suffering of the victims is (at least remotely) to have the chance that we are among the many who are surrounding them as a cloud of support and encouragement in their dealing with their suffering. For the most of us, the “ordinary people” without any significant and immediate capacity to directly respond to the events and people personally affected by this tragedy, that is noble and compassionate.

Prayer is a gesture of solidarity by those who can do little more than such a gesture. It’s an expression of mercy. But mercy is more than compassion. It’s also a desire to end the suffering of the other, if that is within the person’s power. Ah, there’s the rub. “Thoughts and prayers” are good and holy, if that’s all the person can offer to the victim of a man-made tragedy, like a school shooting. But they are perhaps not quite so good and holy if they are an empty offering by those in a position to address the situation, both for the victim of this tragedy, and to prevent future similar tragedies with future victims. Political and social leaders of faith are certainly entitled to extend gestures of thoughts and prayers. But they are not entitled to hide behind that gesture when they do have the power, and therefore the duty, to do more.

“Thoughts and prayers” have been offered to the victims of tragedies for many, many years. And again, rightly so. But as it became clear that these were code words by politicians for “but although we’re responsible for fixing this problem, we’re going to use these words to avoid fixing this problem,” then the phrase “thoughts and prayers” took on a very negative connotation. As cynicism, distrust, and frustration with politicians has grown, and especially as the political divide in our culture has widened, “thoughts and prayers” has come to embody the willful ineffectiveness of government to pass legislation our country needs (besides immigration reform, healthcare reform….). Of course, rushing to pass policy riding on the wave of national outrage is not likely to be the right path, either, even though it satisfies the sentiment that at least something was done, even if it was the wrong thing.

Thoughts and prayers are not a substitute for doing one’s duty in pursuing the right and true solution to the gun-violence problem we have, particularly as it manifests in school shootings. Yes, politicians of faith should offer their thoughts and prayers, but the point is that (if they mean it, and want to avoid an accusation of religious hypocrisy) they cannot stop there. Again, this post isn’t about what politicians should do. It’s about why politicians offering their “thoughts and prayers” elicits such bitter response.

However, for you and me, we offer our thoughts and prayers. We’re not politicians, we’re not local Floridians. Sure, we might send a card or online message. But while we send our thoughts and prayers to the victims of yesterday’s school shooting, and the victims of all the past mass shootings, it would perhaps be more noble to actually offer prayers rather than just a vague promise to do so.

“May God heal the broken-hearted and comfort the sorrowing as we once again face as a nation another act of senseless violence and horrifying evil.” – Archbishop Thomas Wenski of Miami

Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord. And let the perpetual light shine upon them.

And perhaps it would be more noble to actually think of what we might do. Certainly many parents hugged their children tighter last night. Hopefully they also told them to play with the lonely kid at school, and to be kind to the classmate that everyone picks on. Hopefully teachers and classmates and even other parents know what kids are having difficulties at home, and venture to offer support and love, and reminding them of their dignity and gifts. And hopefully school staff are also vigilant of students displaying signs of emotional and psychological illness, signs of destructive, violent, and angry impulses, and aggressively seeking for them the help and attention that they need. Perhaps they can be rescued in all the ways in which past shooters have been failed in getting them the care and concern that their dignity deserved, before the unthinkable happened.

Perhaps also this will be the catalyst to begin concrete initiatives to do what can be done, not just to get the mentally ill the help they need, but to prevent them from having the opportunity to repeat what happened yesterday in Florida. What can we do before the next potential school shooting? We don’t need more children victims, or mourning and grieving parents. My thoughts and prayers are with them. May the Lord Jesus, who wept at the death of his friend Lazarus, and the Mother of Jesus, who stood at the foot of the cross of her son, bring consolation to the parents, families, and friends of those who died, and ease the suffering as they prepare to lay their children to rest. May God guide us in truth, wisdom, and grace to prevent future tragedies like this one.

On Communion and Happiness

Last week I was going to share an article on ecumenism and the resentment some (many?) people have toward the Catholic Church’s traditional practice of “closed communion” (meaning the Church restricts licit reception of communion to only Catholics, and only those Catholics that are not conscious of any mortal sin on their soul). The comment I was typing to share the article was approaching the length of the article itself, and I deleted the whole thing and moved on, without sharing either comment or article (which is how I spend a lot of time on Facebook, to be honest).

Last week I was going to share an article on ecumenism and the resentment some (many?) people have toward the Catholic Church’s traditional practice of “closed communion” (meaning the Church restricts licit reception of communion to only Catholics, and only those Catholics that are not conscious of any mortal sin on their soul). The comment I was typing to share the article was approaching the length of the article itself, and I deleted the whole thing and moved on, without sharing either comment or article (which is how I spend a lot of time on Facebook, to be honest).

It was the Plan, apparently, because this morning I was about to type a new post about happiness, and in my mind it immediately connected with that prior post I didn’t post.

What’s the connection? It’s about what we seek, and that much of what we seek is not what we should seek, but should be the fruit of what we should seek.

First, I’ll go back to that prior post about the Catholic Church’s teaching on closed communion. To begin with, we have to remember the early beginnings of the Church. There were the Apostles and close, faithful followers of Christ, who stayed with Him despite His difficult messages and despite the persecution and fear. They “were of one mind and one heart,” truly in communion with one another–and most importantly–with God through the grace of the sacrament of communion and the witness of how they lived their lives. There was truly an integrity and communion between their lives, their faith, their community, and their Lord. When there was a rupture in this communion, it was obviously a point of distress. It created a scandal (“stumbling block”), both within the community, and in the witness of the community to outsiders, to have such a rupture. St. Paul is very direct in addressing such a scandal:

It is actually reported that there is immorality among you, and of a kind that is not found even among pagans; for a man is living with his father’s wife. And you are arrogant! Ought you not rather to mourn? Let him who has done this be removed from among you.

And then came others who wanted to be part of this little community of “the Way.” Well, to do that, they needed a sponsor in good standing in the community to vouch for them, and to help them learn about how to live, what to believe, what communion is between the believer and the community and the believer and God (hence, sacramental sponsors have to be more than just “Catholic,” they have to live the faith with integrity). This became even more important when persecutions meant that infiltrators might betray the members of the group to the public authorities. And then splinter groups started forming who had theological opinions different than the sense of the faithful of the apostolically-formed communities (who, though they were geographically separate, were united in a single faith, as attested to, for example, by the writings of St. Irenaeus of Lyons). Of course, one of the key beliefs of the Church was the reality of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. Although the formulation of just *how* Christ was present in the Eucharist wasn’t pursued as a question at the time, the belief that he *is* present was essential. Even St. Paul, writing to the Corinthians, made it clear:

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself.

The Church through her holy Tradition maintains this early disposition about receiving communion: that only those in full communion of FAITH and WITNESS–of believing all that the Church teaches as true (especially about the Eucharist), and having nothing scandalous on their conscience that would separate them from the community–are admitted to the celebration of communion.

That’s the background for my point. As I often lament, “God has blessed me with many gifts, but being succinct is not one of them.”

I would propose (I think without much disagreement) that there is much more “unworthy” (or in technical terms, “illicit”) reception of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church than any previous time; “unworthy reception” meaning that communion is sought and received by those who are not in full communion with the Church, either by a break in faith, or a break in witness (mortal sin). And my point of all this is that this is why: the general pulling apart of the internal and external of everything.

The most commonly encountered example of this is our relativist modern society:

it doesn’t matter what you believe, as long as you’re a basically good person. (see: Moralistic Therapeutic Deism). Of course, what a “basically good person” is, we don’t completely agree on, but for the most part, it’s that you leave everyone else to believe and live however they wish, and keep what you believe to yourself. If what you believe infringes on anyone else believing and living however they wish, then there is a problem with what you believe. You can go to what church (or synagogue, or mosque, or temple, or whatever) you want, and have in your heart whatever you want, and whatever you believe ends with you. Outside you, it’s not your church or beliefs that matter, it’s social and government policy that matters. That’s how we all get along (unless your beliefs try to get out into society). On this topic I HIGHLY recommend Matthew Leonard’s podcast with Andrew West on “Church and State.” (You can ignore his over-hyped title, just listen to the interview).

So you would reasonably think that at least within the Church–within the Church building itself, within the liturgy itself–that this would be a “safe space” where the Catholic Church has the authority to say to her own children (and guests): this is the truth of what we believe, and this is what we should do with it. That at least here in church, among our own people, we would honor the Church’s own teaching, that if you are not in full communion with the Church (community) in what the Church believes and teaches, and/or if you are not in full communion with the Church (community) because of mortal sin, do not approach to receive and celebrate the sacrament of communion (because you are not *in* communion).

Instead of people taking the integrity of inward reality and outward sign (that is at the heart of what a sacrament is) and bringing an increase of integrity to their life, they bring the dis-integrity of the separation of inward and outward, from life in our society, and apply it to receiving communion. What do I mean? I mean that we bring into our liturgical celebration the worldly mentality that our interior life is irrelevant to our exterior life. As long as we are a “basically good person,” we’re good enough (to be allowed to do what we want, including receiving communion); and that whatever interferes with that (especially if it makes us feel bad) is bad.

But here’s where it ties into the beginning, on the potential post on happiness. Why do people *want* to receive communion? Because it feels awkward and vulnerable (and judged) to *not* receive communion. What will people think of me? (“me” should be a rare thought during the liturgy anyway.) It just makes everything more difficult with people having to pass by me in these narrow pews, and my reason for not receiving communion is not that bad anyway. I’ll just go. (Noooo!)

My Spanish teacher told me it was quite a culture shock when he went to church in the US, compared to Mexico. In Mexico, most people do not receive communion, because they know they shouldn’t. Unfortunately, there is no burning desire for communion that drives them to repent of their sins and come into communion with the Church. In the US most people receive communion, worthy or not. This teacher said when his mother first went to church in the US, she was amazed at how holy everyone must be to all be receiving communion. He had to give her the bad news. Maybe it’s because in Mexico, there’s a strong cultural aspect of Catholic guilt, and in the US, there’s an even stronger cultural aspect of self-esteem (if you want it, go get it).

So we want the outward appearance, the fruit, of communion (approaching and receiving the sacrament of communion), without the inward reality of in fact being in communion. The outward appearance of the Church is as a hierarchical social organization of people who come together to hear bible readings and share in the distribution of bread and wine. But the inward reality of the Church is the Body (and Bride) of Christ; an organic whole, of which all the baptized are sacramental body parts, each with a divinely-appointed and provided-for role in the life of the Body. And the appearance of bread and wine are in (sacramental) reality the nourishing and healing of the spiritual life we received at baptism–He whose life we have received and live nourishes us repeatedly with his Body and Blood to become ever more (because we live in material and passing time, we need continually renewed and returned to the source) in communion with Him and with the other members of His mystical body, as an organic communion of a whole, of which He is the Head. (In the Catholic faith, it’s SO MUCH MORE than just a symbol! But if you’ve detached yourself from the communion of the Body, by a break of faith or a break of witness, it’s a fatal break, as you’ve detached yourself from HIM who is the source of life!)

We go after the shiny wrapper and throw away the valuable contents. We want the wrong thing. Our want is too superficial, and God calls us to the deep reality of which we only want the outward sign. We shouldn’t want just the sacrament of communion (although it is itself no small thing: it is the source and summit of the Christian life); we should want *communion itself*, profound unity in self-giving (kenotic) love with our community (the Church in this world, and in purgatory, and in heaven, all members of one Body!) and with our Lord, and even within ourselves: intra-personal and interpersonal divine peace, which we can only truly have through the divine gift of the sacramental grace and living according to (and outward from) that grace.

And therein lies the rub.

We want to receive communion, and we want it on our terms, defiant that it has its own nature which does not submit to our terms. We want to receive communion and ignore the invitation to the deeper reality that the outward fruit of communion truly means and relies on.

We want happiness, and we want it on our terms, defiant that it (and the human person) has its own nature which does not submit to our terms. Happiness is actually the fruit of holiness, which is a participation in the divine life. When we experience friendship, love, joy, pleasure, peace, comfort, in any measure, we seek these as happiness; and they are: they are “passing participations” in what God is. But happiness is not the goal: holiness is the goal, an *abiding* and profound (and ultimately, eternal) participation in the divine, the “happiness of the saints.” These things make us happy because they are what we are made for. But when we seek happiness itself, we miss, or worse: we seek happiness in anti-divine ways that ultimately bring us (and often others with us, since we are all connected) profound unhappiness. At worst, our grasping at some improper way of pursuing happiness costs us (and perhaps others) the eternal happiness for which we were made. But if we seek holiness, we get happiness thrown in, because happiness is the fruit of holiness.

Ultimately, we as human beings are called to participate in God’s divine life. He didn’t make us because he needed worshipers for his frail ego. He didn’t make us to spend eternity in this passing world. He didn’t make us to lose ourselves by merging into Him. He made us to be in enduring, intimate (“nuptial”) relationship with Him, as He is in Himself: to be drawn in, through His Son, into the very exchange of divine love that is the Holy Spirit: the Spirit of Truth, the Spirit of Unity, the Spirit of Divine Love. The Holy Spirit is a Person of the Trinitarian God, and we are called into the fullness of that Spirit. That fullness is the fullness of happiness, the fullness of love, the fullness of communion, the fullness of friendship, joy, pleasure, peace, comfort (and all the rest) which truly satisfies the longing of the human heart, because it was for this that we were made: perfect communion, perfect happiness–the image and likeness of God.

Let us not prefer the wrappers to the reality. Let us not prefer the illusion (or lie, or redefinition) of communion for the authentic reality of divine communion. Let us not prefer the appearance of goodness for the authentic reality of divine goodness. Let us not prefer the consequence of happiness for the cause, which is the authentic reality of divine holiness. We want the wrong thing, and we were made for more. “Be holy, for the Lord your God is holy.” And you will be happy.