The Seventeenth Sunday of Ordinary Time (Year C)

Genesis 18:20-32

Psalm 138:1-2, 2-3, 6-7, 7-8

Colossians 2:12-14

Luke 11:1-13

Our gospel reading today begins, “Jesus was praying in a certain place. And when he had finished, one of his disciples said to him, ‘Lord, teach us to pray, just as John taught his disciples.’” We often don’t think of John the Baptist as a man of prayer. He was a man of calling people to repentance, and preparing them to receive and follow the Lord. But John also had disciples, and taught them to pray according to his own mystical relationship with God.

And that’s what this disciple is asking Jesus. The first thing we should contemplate is that the disciples saw Jesus at prayer. They see the way Jesus prays, and it’s profound, it’s deep communion between Jesus the divine Son and God the Father, in a relationship unprecedented in human history. The disciples see Him at prayer, and want to Him to teach them to pray like Him. Our Gospel reading is the answer Jesus gives to this request. It’s not about adopting a technique or style of prayer. It’s about entering into the relationship of prayer between each of us and our heavenly Father, the relationship Jesus the Son invites us into. Jesus has three parts to His lesson on prayer.

In the first part, Jesus teaches them what we call the Lord’s Prayer. Of course, this version of the Lord’s Prayer in the Gospel of Luke is different than the longer one we usually pray, which is from the Gospel of Matthew. This shorter version has 5 petitions, as opposed to the 7 in Matthew’s Gospel. In Jewish Tradition, and in Christian Tradition, there are often longer and shorter versions of the same basic prayers. We should reflect on this prayer that Jesus gives us as the example for praying to the Father.

The first two petitions focus on God. First, “Father, hallowed be your name” (or, “may your name be hallowed”). God’s name, which is different variations of “I AM,” “God is with us,” “God Saves,” “God Most High,” should be held as holy, as set apart from our everyday vocabulary, like we put the special dishes in the special cabinet so they don’t suffer the wear and tear of how our everyday stuff gets treated. That doesn’t mean we don’t call on God’s name every day! It means that we treat it special every day! And we pray that His name would be hallowed and worshiped by all on earth, the one true God, Whose glory fills heaven and earth.

The second petition, “your kingdom come.” God’s kingdom is where God reigns, and all give Him glory, and follow His law. In one sense, His kingdom is heaven, the kingdom of the angels and saints. In another sense, His kingdom is here on earth. When Jesus was before Pontius Pilate, Jesus said, “My Kingdom is not here.” Because it’s the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost that fills the earth and transfigures it after the pattern of Jesus. By appearance, he looked like everyone else. But in the truth of the Spirit, He is the power and wisdom of God. We participate in the life in Christ: we appear to live earthly lives like everyone else; but in the Spirit, we are united with God, we make our choices and shape our character and our lives by the truth and laws of His kingdom, and so in living by the Holy Spirit, we make God’s kingdom manifest. We pray that His kingdom come and unite all on earth into the blessings of heaven; we pray that the day of our Lord Jesus Christ—judgment day—come, and that we be found worthy to enter into the fullness of His kingdom for eternity. That’s a bold prayer. Jesus teaches us to pray it. But he also teaches us to always be ready for that day, lest we find ourselves rejected.

Those are the first two petitions, which put our attention on God. The other three petitions ask God to put His attention on us.

“Give us each day our daily bread.” Give us what we need to live, to be saints. The Greek word translated “daily” is a play on words: it could be epi-ousios, which means “supernatural,” or epi-iousios, which can mean “every day”. The word play is that it’s both. It refers to the daily care of God; the fulfillment of our spiritual and physical needs, and of course, the Eucharist, the supernatural and daily bread that strengthens us in our holy communion with God and the communion of the saints.

Then he teaches us to pray, “and forgive us our sins for we ourselves forgive everyone in debt to us.” It’s an interesting thought, that it equates sin in the first part, with debt in the second part. When someone sins against someone else, they incur a debt (of justice, and more so, of love) because they have not acted toward them as the divine law requires. When someone sins against us and incurs such a debt, our response is (or ought to be) to forgive that debt. God is generous with his forgiveness toward us, and that inspires us to be generous with our forgiveness toward others.

And the final part of the prayer, “and do not subject us to the final test.” Or Matthew’s version, “And do not lead us into temptation.” Of course, God does not tempt us to sin. But God does test us, our patience, our character, our faithfulness—not to discourage us or get us to fall, but to strengthen us and help us to grow. We can be tempted to get bitter, to get frustrated, to give up our faith, to try to go around God to get what we want. That’s the ever-present temptation to sin, especially in suffering. But this is our prayer that whatever we endure, we are asking God to give us the grace to respond by growing in faith and love and holiness. So the Lord’s Prayer is the first part of Jesus’ answer.

The second part is this story about the man who must go bother his neighbor during the night. The lesson Jesus is giving us isn’t that God is going to be slow to respond. The lesson is that we must be persistent in our prayer. The Greek word being translated “persistence” is like “shameless.” The person knocking knows that he’s bothering his neighbor, but he’s in such dire need that he’s going to persist, he’s going to continue past the point of being annoying, until he gets what he needs; he tosses the rules of proper respect aside and just keep begging of God shamelessly, persistently, until God responds.

And the third part of Jesus’ instruction: “What father among you would hand his son a snake when he asks for a fish?” No one, of course! But the moral of the story is that if we sinful human beings, who love our children, give them what they need as generously as we can, and don’t give them the things that would hurt them, how much more so does God, the perfect Father in heaven, do better even than that? The most important thing we could ask God for is Himself, the gift of the Holy Spirit. And He gives Himself to us generously, even when we’re not smart enough to ask for it! So if God is not answering our prayer, either He is testing us, wanting us to grow, or what we’re asking for is not good for us, and God is not going to give it to us, or He’s given us an even greater gift, and we’re too focused elsewhere to have noticed the better gift. So that’s the Gospel. A lot going on in a few short lines, as you would expect when you ask Jesus to talk about prayer!

And just a moment on our First Reading before we end. Abraham’s haggling with God to save Sodom demonstrates the life of prayer that Jesus teaches us: Abraham’s relationship with God, built on a solid prayer life; his humble knowledge of himself in light of God’s glory; and Abraham’s patient persistence in prayer to intercede on behalf of the people in Sodom, particularly his loved ones.

As we know, God still destroyed Sodom. Ultimately our prayer isn’t, “God, I want you to do this.” Ultimately, our prayer is “God, I want you to do this… but… not my will, but thy will be done.” The more we learn to have our heart in tune with God’s heart, we will have more of our prayers answered, because we will want what he already wants to give us. The further along our spiritual journey of being who he made us to be, the more often it will be our experience that we ask and we will receive; that we seek and we will find; that we knock and the door will be opened to us. For everyone who loves God and asks, receives; and the one who loves God and seeks, finds; and to the one who loves God and knocks, the door will be opened.

God does sometimes do this, when we’re in a position of really not paying attention to Him, and he really wants to get something through to us. This is a good technique for communicating, but it’s not good for formation, which is what he really wants. He wants to form us into saints by our free will, by our decision to direct our faith, hope, and love to him. He wants us teach us to be His dance partner, to live gracefully, and to be so attuned to His will, that He need only give us the slightest gesture of how to move, how to serve Him, and we respond with grace and joy.

God does sometimes do this, when we’re in a position of really not paying attention to Him, and he really wants to get something through to us. This is a good technique for communicating, but it’s not good for formation, which is what he really wants. He wants to form us into saints by our free will, by our decision to direct our faith, hope, and love to him. He wants us teach us to be His dance partner, to live gracefully, and to be so attuned to His will, that He need only give us the slightest gesture of how to move, how to serve Him, and we respond with grace and joy.

Your neighbor, whom you are obligated to love as you love yourself, is also the people you dislike, the people you’ve been having fights with, the people you ignore, the people who are strangers. And especially, your neighbor is anyone you see who is in need: the vulnerable, the outcast, the poor, and frightened. Your neighbor is every person who is made by God in His image, which is every person. What does it mean to love your neighbor? To do as the Samaritan did: to show mercy, to personally sacrifice, to put yourself out and become vulnerable, to invest yourself (in love) in their well-being and flourishing.

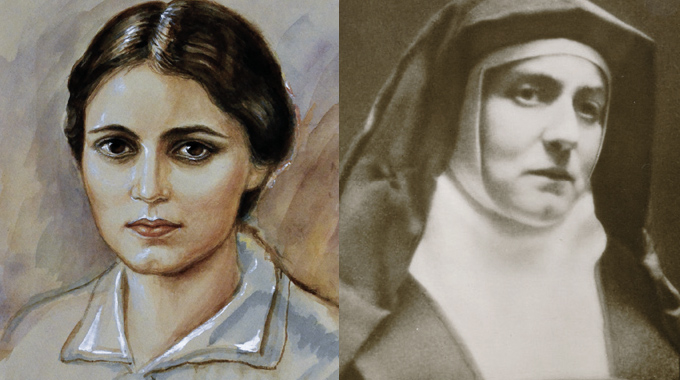

Your neighbor, whom you are obligated to love as you love yourself, is also the people you dislike, the people you’ve been having fights with, the people you ignore, the people who are strangers. And especially, your neighbor is anyone you see who is in need: the vulnerable, the outcast, the poor, and frightened. Your neighbor is every person who is made by God in His image, which is every person. What does it mean to love your neighbor? To do as the Samaritan did: to show mercy, to personally sacrifice, to put yourself out and become vulnerable, to invest yourself (in love) in their well-being and flourishing. I’ll end with this quote from another Theresa, St. Theresa Benedicta of the Cross (the religious name of St. Edith Stein), who was a Jewish-convert to the Catholic faith, and martyred by the Nazis in Auschwitz. St. Theresa Benedicta of the Cross wrote this, which beautifully summarizes our reflection on the Good Samaritan: “

I’ll end with this quote from another Theresa, St. Theresa Benedicta of the Cross (the religious name of St. Edith Stein), who was a Jewish-convert to the Catholic faith, and martyred by the Nazis in Auschwitz. St. Theresa Benedicta of the Cross wrote this, which beautifully summarizes our reflection on the Good Samaritan: “