First Sunday of Lent, Year A (https://bible.usccb.org/bible/readings/022226.cfm)

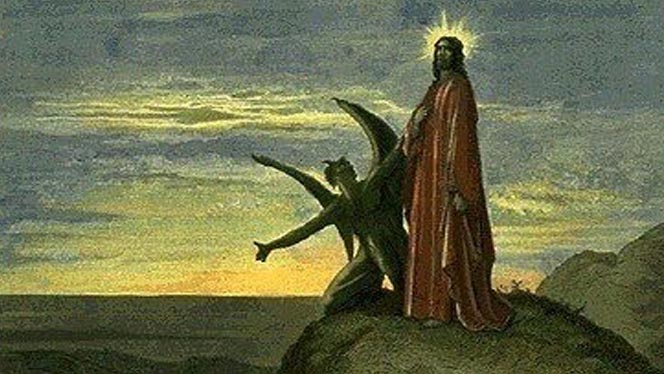

Each liturgical year, we work through a different Gospel book, and each year the first Sunday of Lent features the temptations of Jesus in the desert, or wilderness. Our reading can raise certain questions: why does Jesus go out into the desert? Why is he there for 40 days? And what is the significance of these three temptations? Are they really temptations for Jesus?

The first two of these we can take care of in quick order. When the scriptures use the number forty, it refers to a period of preparation, testing, and purification. In a similar way, the desert, too, was the place for testing and purification. It was a reminder of the years of the Exodus, as God tested, purified, and prepared his people to inherit the Promised Land. So Jesus, after his Baptism, was driven by the Spirit into the desert, fasting for forty days and forty nights, like Israel’s forty years in the desert, preparing him for the challenges of his earthly ministry, purifying his will, that he would fully embrace the mission from the Father: to be the Lamb of God, who by his cross and resurrection, would take away the sins of the world.

So why these particular temptations? “‘If you are the Son of God, command that these stones become loaves of bread.’” Jesus was human and had been fasting for forty days. His natural biological temptation, quite understandably, would have been to satisfy his hunger with food. But he responds instead by quoting Deuteronomy: “It is written: One does not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes forth from the mouth of God.’” “Then the devil…made him stand on the pinnacle of the temple, and said to him, ‘If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down. For it is written: ‘He will command his angels concerning you and with their hands they will support you…’” Interestingly the devil quotes from the Scriptures. But Jesus is being tempted with pride: show everyone your power, and they will follow you. But Jesus again quotes Deuteronomy, “You shall not put the Lord, your God, to the test.” His mission wasn’t to overwhelm the people’s need for faith with his divine powers, but to woo them by winning their free choice to follow him, by his signs, by the wisdom of his parables, by his love for them. “Then the devil…showed him all the kingdoms of the world in their magnificence, and he said to him, ‘All these I shall give to you, if you will prostrate yourself and worship me.’” The devil is showing Jesus all the kingdoms—all the souls—of the world. He says, “I will give them to you; all you have to do is worship me.” It’s the temptation to save humanity without the cross. Jesus responds: “Get away, Satan! It is written: ‘The Lord, your God, shall you worship and him alone shall you serve,’” again quoting Deuteronomy.

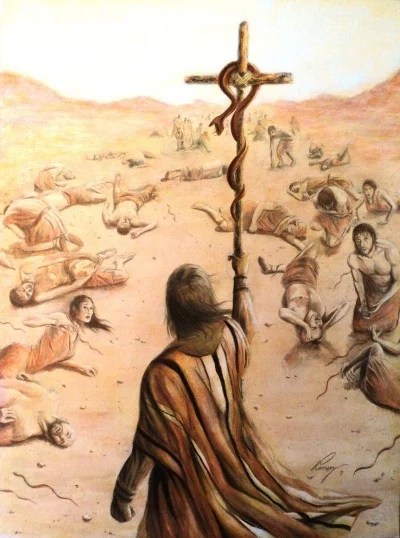

St. Peter will a bit later repeat Satan’s temptation to bypass the cross, and Jesus will rebuke him with a similar response: “Get behind me, Satan.” Jesus will do the Father’s will, in the way the Father wills. He will lay down his life, and show us the depths of divine self-giving love.

These three temptations of Jesus relate directly to what are called the “triple concupiscence,” the three primal weaknesses in human nature. The first letter of John (2:16) describes this three-fold weakness: “the lust of the flesh, and the lust of the eyes and pride of life.” Pleasure, Possession, Pride.

And they go back even to the temptation in the Garden of Eden, which is our first reading. We can see how the devil twists Eve’s way of looking at the forbidden tree. “The woman saw that the tree was (1) good for food, (2) pleasing to the eyes, and (3) desirable for gaining wisdom.” So, first, the “lust of the flesh,” Eve saw that the fruit was good for food. And in our gospel reading, Jesus was tempted to turn stones into bread to satisfy his bodily appetite. Second, the “lust of the eyes.” Eve saw that the fruit was “pleasing to the eyes,” and Jesus was tempted by the presentation of all the kingdoms of the earth, and all the souls he loved and wanted to heal and save. And third, “pride.” Eve saw that the fruit was desirable for gaining wisdom (for becoming like God, but apart from God). And Jesus was tempted to exercise power in human terms, by commanding the obedience of humanity by force by a display of his supernatural power.

Any temptation we endure is in a sense one of these three areas of temptation: pleasure, possession, or pride. During the forty days of Lent, the Catechism tells us, the church “unites herself each year to the mystery of Jesus in the desert”. How do we do that during Lent?

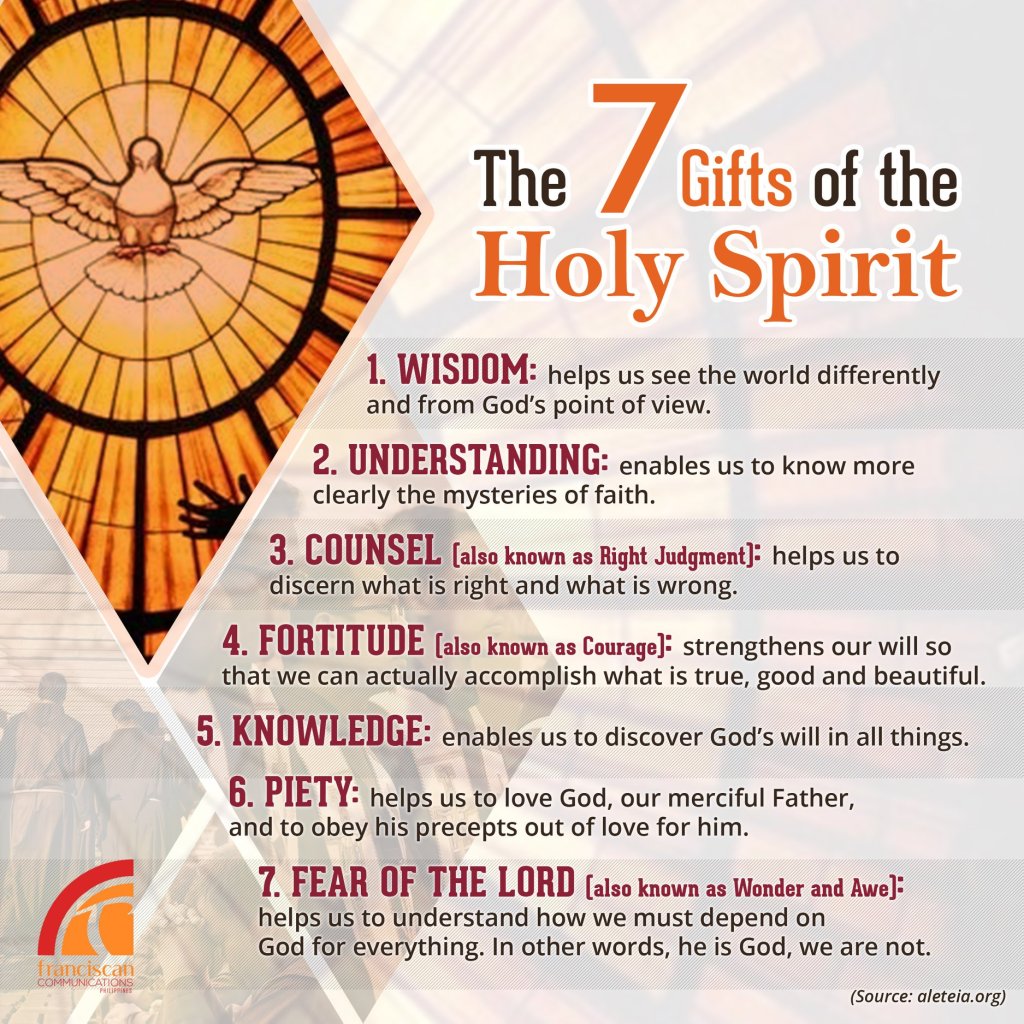

Every year we have the gospel reading for Ash Wednesday: The teaching of Jesus on Prayer, Fasting, and Almsgiving. We might think of these as three basic Lenten penances. We might better think of these as Christian disciplines to do all year round, but with increased attention to them during Lent. But even more importantly, these three practices correspond as the antidote to the triple concupiscence and Jesus’ three temptations in the desert. Jesus calls us to fast, to overcome our disordered desire for pleasure, especially bodily pleasure. And He calls us give alms, to the poor, to the church, fasting from the desire of possession, detaching from worldly priorities, serving God and not mammon. And he calls us to pray. Humility is the antidote to pride. When we pray, we acknowledge that God is God and we are not; we are dust and to dust we will return.

I want you to think about the responses Jesus gives, scripture verses he quotes to rebuke the devil in these temptations. Because all of our human sins can be categorized as either a disorder of lust of the eyes, lust of the flesh, or pride of life—pleasure, possession, or pride. And so, Jesus gives us a cheat-code against our temptations. We can rebuke the tempter with the same rebuke that Jesus used, the scripture verses he used, and we can share in Jesus’ victory over temptation and sin.

When we are tempted to indulge in sins of the flesh, we can respond, “(It is written,) ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.’” When we are tempted to greed, envy, jealousy, other sins of the eyes and possession, we can rebuke the enemy, “You shall worship the Lord your God and him only shall you serve.” And when you are tempted to pride, you can respond, “it is written, ‘You shall not tempt the Lord your God.” I would encourage you to memorize these three verses and wield the sword of scripture as the weapon against the enemy that it is. But if you can’t remember the verse you need in the moment of spiritual battle, you can always fall back on, “Get behind me Satan.”

So, we can unite ourselves to the mystery of Jesus in the desert…and on the cross! It’s ultimately on the cross that Jesus completely overcomes these three temptations (1) his lack of pleasure, in the sufferings of the crucifixion (2) his lack of possessions, crucified naked, and even giving away his mother; (3) and his definitive defeat over pride by his humility. Equipped with our Lenten penitential practices, we will be able to resist these three essential temptations of the devil, and of the world.

In Greek mythology, creatures called the sirens lived on an island and, with the irresistible spell of their song, they lured sailors to their destruction on the rocks surrounding their island. When Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s Odyssey, was sailing past that place, he had himself tied to the mast and wax put in the ears of his sailors, so that they might not hear the sirens’ tempting singing. But King Tharsius chose a better way past the island. He took along with him the great Greek musician Orpheus. Orpheus took out his lyre (his harp) and sang a song so clear and ringing that it drowned out the sound of those lovely, fatal voices of the sirens. The best way to break the charm of this world’s alluring voices during Lent is not trying to shut out the world, but to have our hearts and lives filled with the sweeter music of true faith, hope, and love: prayer, fasting, and almsgiving. When we are enthralled by our love and desire for heaven, then the alluring voices of the lesser things of this world —pleasure, possession, and pride—will be powerless over us.