Homily for the 2nd Sunday of Advent (Year A readings) (go to readings)

Isaiah 11:1-10

Psalm 72:1-2, 7-8, 12-13, 17

Romans 15:4-9

Matthew 3:1-12

In 1830, George Wilson was convicted of robbery the U.S. Mail and endangering the life of the carrier in Pennsylvania and was sentenced to be hanged. At the request of George Wilson’s friends, President Andrew Jackson issued a pardon for Wilson. But he refused to accept it. The matter went to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Marshall wrote in the court’s decision that Wilson would have to be executed. “”A pardon is a deed, to the validity of which delivery is essential, and delivery is not complete without acceptance. It may then be rejected by the person to whom it is tendered; and if it be rejected, we have discovered no power in this court to force it upon him.” If it is refused, it is no pardon. Hence, George Wilson must be hanged.

Last week we talked about the preparation of our hearts for the Advent, the coming to us, the arrival of Jesus. We join in the generations of anticipation experienced by ancient Israel. We as the Church want to always be prepared for his final coming, whatever day and hour that might be. We prepare our hearts to receive him every day in the Eucharist, and in his presence within us in the Holy Spirit. In today’s gospel reading for the second Sunday of Advent, we are being prepared for the arrival, the beginning in the world, of the earthly ministry of Jesus, the message of Jesus.

Saint John the Baptist is preparing people for the most important event in the history of existence. In the long history of Israel, there was a promise at the very start. The promise from the moment of the Fall of Humanity in the Garden of Eden, and our expulsion from Paradise. And that promise begins back “in the beginning”–in Genesis 3–that despite humanity’s disobedience to God, that God would fix it. That this condition of separation of humanity from God would be healed, and we could repent and be reconciled to God, at long last, restored to Paradise. God said in Genesis 3 that there would be an offspring of the woman who would crush the head of the offspring of the serpent. That God would prepare humanity in a “school of trust” to learn that God is for us, that God wants us to have happiness and fulfillment, and that we do not need to go outside of God’s will to take care of ourselves and our deepest needs.

[Note: The “school of trust” is a reference to the work, “The Second Greatest Story Ever Told” by the Marian priest, Fr. Michael Gaitley, about the Divine Mercy devotion.]

This promise was the hope of the “Anointed One,” the “Messiah” in Hebrew, the “Christos,” in Greek. Throughout Israel’s history, other promises got braided together with this one.

King David was promised that a Son of David, the Davidic dynasty, would sit on the throne of Israel in glory forever. But when Israel returned from the Babylonian Exile, the new king was not of David’s line, nor was any king afterward. And so, the promise of the long-awaited true King of Israel, the promised Son of David, was added to the Messianic hope, the one who would be anointed to fulfill God’s plan and God’s promise.

After the decline of Israel from its glory during the reign of King David and King Solomon, Israel broke into two kingdoms. The powerful Assyrian Empire destroyed the ten tribes of the northern kingdom, dispersing them throughout all the nations of the world, leaving only the two tribes of the southern Kingdom of Judah (or “Judea,” in Greek/Latin). And so, another part of the hope for the Messiah was that he would restore Israel’s greatness and the unity of the twelve tribes into a single kingdom, and all the world would worship the one true God of Israel.

And lastly, although it was more subtle, God himself had said, in condemning the wicked “shepherds” of Israel who mistreated the flock of God’s people, that God himself would come and shepherd his people, that he would search for the lost sheep and bring them back, that he would bind up those who were wounded, and feed those who were hungry, and gather them to have them graze in green pastures in their own land. And so, there was also the revelation that the Messiah would also, in fact, be divine, be God himself.

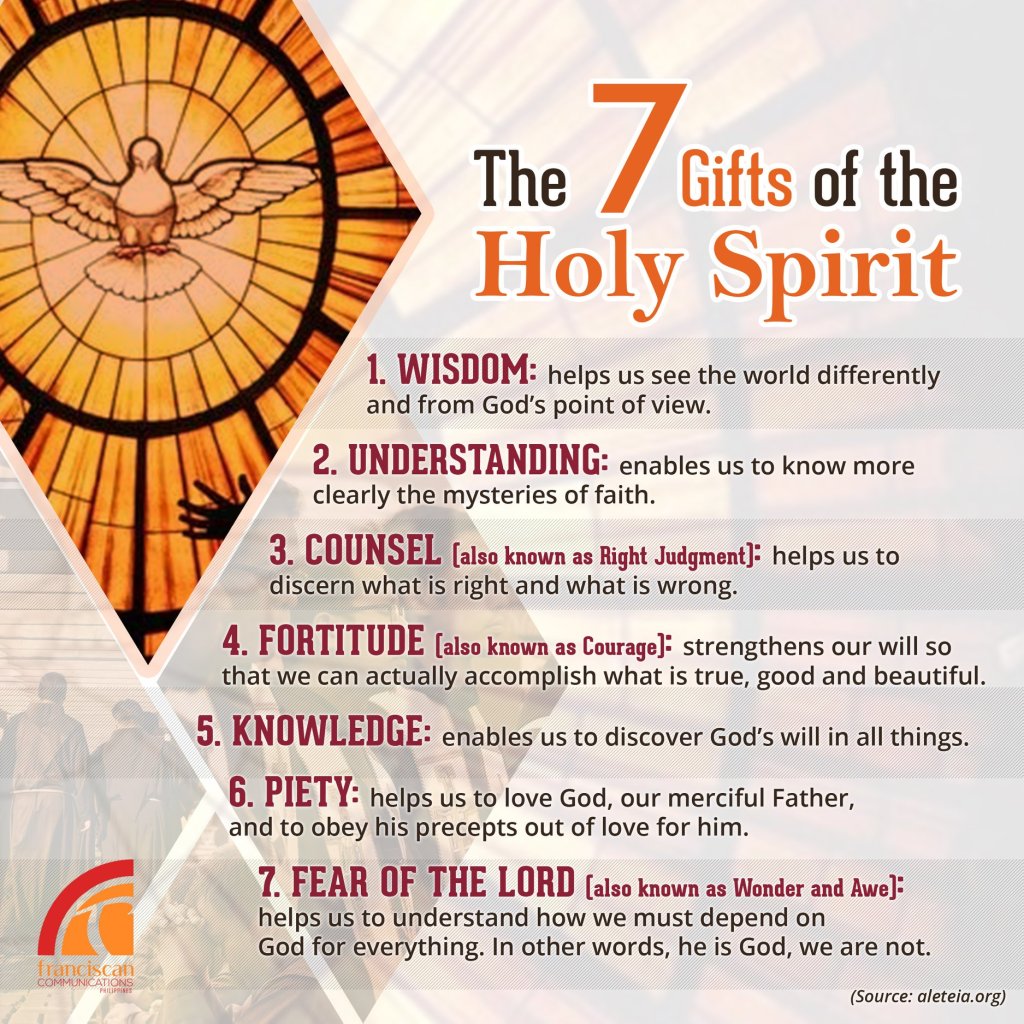

And so, St. John the Baptist, looking and acting a lot like the Old Testament Prophet Elijah, who was prophesied to return to herald the coming of the Messiah, was out in the wilderness by the Jordan River, proclaiming “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!” The Messianic age, the promised return to paradise, as we see in the strange images of the First Reading from the Prophet Isaiah. “On that day,” Isaiah, says, “a shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse, and from his roots a bud shall blossom.” And this is where we get the traditional list of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit (wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord, or reverence), which will rest on this long-awaited bud, who would grow from the stump of Jesse, the father of King David. Isaiah is affirming the promise of the Son of David, the Messiah, the Good Shepherd. And one of the marks of the Messianic age, again, apparently missed by the Israelites (based on the events in the synagogue in Nazareth), but we can see more clearly from our perspective looking back, is that the Messiah will draw the gentiles to himself as well. Which makes sense. If the ten northern tribes, dispersed among all the nations of the world, are to be restored by the Messiah, then the new covenant of the Messiah would have to include all the nations, the whole world. It would be one, holy, and catholic (“universal,” from the Greek, “katholikos”) covenant family.

John not only proclaims the Messiah is near, to “Prepare the way of the Lord,” but he proclaims how we are to do that. “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!” Why? Because the Messiah is promising mercy, healing, forgiveness, and reconciliation. We desire the wrong things, we love the wrong things, we say and do the wrong things. Our heart is all messed up. He’s promising a new heart. The proclamation of the good news is that God is offering everyone a free heart transplant. But that’s only good news to someone who knows they need a new heart. The invitation of mercy is only good news to those who are aware they need mercy.

Later in the Gospel of Matthew, the Pharisees are going to ask the disciples of Jesus, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” And Jesus will answer them, “Those who are well do not need a physician, but the sick do… I did not come to call the righteous but sinners.” Jesus is not saying that the Pharisees are righteous, but that because they believe they are righteous, they are failing to seek out the physician for themselves. They believe their heart is fine, and so are refusing the freely available heart transplant. They are refusing (like George Wilson) the pardon for the death sentence for their wrongdoing, and so the consequences of their wrongdoing remain upon them.

John is not offering a baptism for the forgiveness of sins, which will only come later with Jesus and the gift of the Holy Spirit for the forgiveness of sins. John is merely offering them a baptism of repentance. A humble, contrite confession that they need a savior, a messiah, a spiritual physician, a pardon, a heart transplant. So that, with them being so urgently and painfully aware of their need, they will hear of the good news of the arrival of the long-awaited Messiah, the Christ, and they will rejoice at the good news, they will seek to find him, and all will be made new.